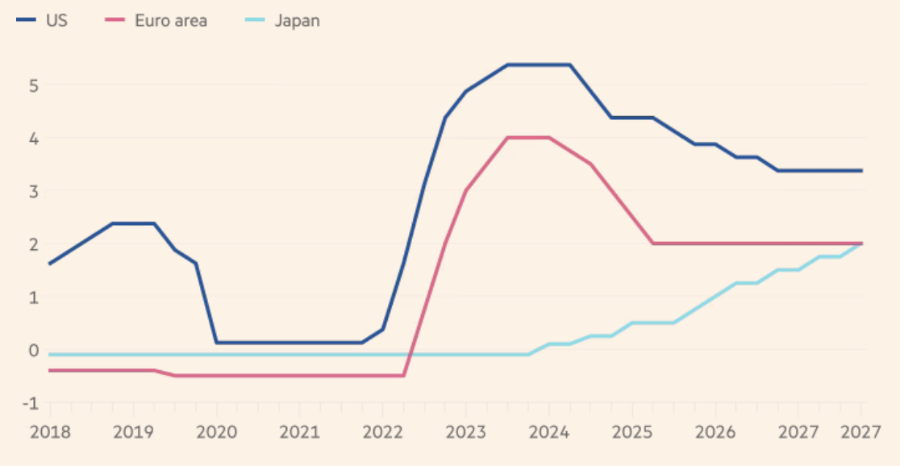

The latest forecast from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) suggests that major economies around the world will complete their monetary-easing cycles before the end of 2026.

Accordingly, major central banks have little room left to continue monetary loosening even as economic growth slows.

The OECD projects that the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) will cut interest rates only two more times in 2026 before keeping the federal funds rate in the 3.25–3.5% range throughout 2027. Maintaining rates at this level is intended to balance inflationary pressures from tariffs and the weakening labor market.

The report comes as President Donald Trump prepares to nominate a new Fed chair, who will face significant pressure to reduce borrowing costs. Meanwhile, the Fed will hold its final monetary policy meeting of 2025 next week, and markets are expecting a 0.25 percentage point rate cut.

In the eurozone and Canada, the OECD does not expect any further rate cuts next year, while Japan is projected to continue tightening monetary policy as inflation in the country stabilizes above the 2% target.

The Paris-based institution also expects the Bank of England (BOE) to halt rate cuts in the first half of 2026, while the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) is predicted to reach the same point in the second half of the year.

The OECD’s new forecast shows that in many countries, interest rates need to remain higher than pre-pandemic levels to control inflation, partly because public debt levels are higher than before. In many advanced economies, real interest rates are now near or within estimated ranges of the real neutral rate, and all advanced economies are expected to reach those levels by the end of 2027.

The OECD report states that the global economy has withstood President Donald Trump’s tariff policies better than initially feared.

Global gross domestic product (GDP) is forecast to grow 3.2% in 2025 before slowing to 2.9% in 2026 and rising again to 3.1% in 2027, in line with the latest forecasts from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). This optimistic outlook is partly supported by the boom in artificial intelligence (AI)-related investment — an activity that is driving industrial production in the U.S. and several Asian economies.

The OECD now projects U.S. economic growth of 2% in 2025, higher than the provisional 1.8% forecast issued in September, with growth expected to gradually rely less on AI investment throughout the year. However, U.S. growth is projected to slow in 2026 as tariff impacts increase, though to a lesser extent than previously expected, with GDP likely to expand 1.7%.

The OECD also raised its 2025 GDP growth forecasts for the eurozone and Japan, with both economies expected to grow 1.3%. Additionally, the report upgraded the outlook for major emerging economies including Brazil and India.

According to the report, the UK economy is expected to perform better in 2026 than earlier forecasts suggested. The OECD estimates that the country’s GDP growth will decline from 1.4% this year to 1.2% next year, but this is still higher than the 1% projection from September.

However, speaking to the Financial Times, Asa Johansson, Deputy Director of Statistics and Data at the OECD, warned that global economic growth remains “fragile and should not be taken for granted.” A sudden repricing of assets — if optimism about AI fades — could be “amplified by forced asset sales” from non-bank financial institutions that have become increasingly interconnected with the traditional financial system, the OECD cautioned.

The institution also urged governments to use the period of relative stability to tackle the growing burden of public debt. Only a few countries, including France, Italy, Poland, and the UK, are planning significant fiscal tightening over the next two years.

According to the OECD, countries such as Germany have the capacity to increase debt and may maintain higher defense spending “for some time.” But even in these nations, rising spending needs for healthcare, elderly care, and climate measures will “ultimately absorb fiscal space.”

Leave a Reply