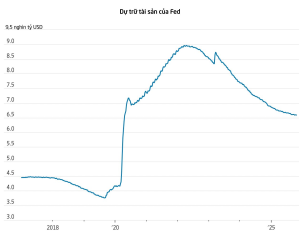

This week, the US Federal Reserve will have to make an urgent decision, not about further interest rate cuts, but whether to stop shrinking its $6.6 trillion balance sheet sooner than expected.

Just two weeks ago, the Fed maintained its stance that it would wait until the end of 2025 to decide whether to stop the “runoff” process, which involves letting securities mature without reinvesting, thereby reducing the size of its balance sheet. In a speech on October 14, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said the end of the process “could come in the next few months.”

However, recent volatility in the currency markets, especially the unexpected rise in overnight interest rates, is leading many analysts and Fed officials to believe that the “curtain call” may need to come sooner.

The reduction of the balance sheet is not directly related to interest rate policy, but is part of an effort to control short-term interest rates, which directly affect consumer, home and business loans. During the financial crisis of 2007-2009 and the pandemic, the Fed expanded its balance sheet by buying large amounts of government bonds and mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

Since 2022, when its balance sheet peaked at nearly $9 trillion, the Fed has begun to let maturing assets automatically exit the system without reinvesting, leading to a decline in bank reserves.

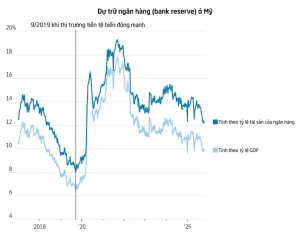

But the process is fraught with risks. If the Fed shrinks its balance sheet too much, the financial system could run out of liquidity, as happened in 2019 when overnight interest rates spiked, forcing the Fed to pump money back in quickly and causing panic in the markets.

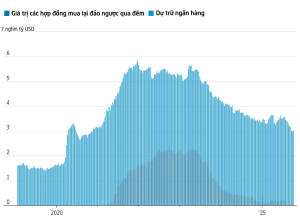

Over the past three years, most of the money flow has come from the Fed’s money market funds, but that source has now nearly dried up, from a peak of $2.2 trillion in 2023 to very little left. Starting this month, every dollar maturing will be withdrawn directly from banks’ reserves.

The recent issuance of more US government bonds has taken more money out of the system, causing interbank rates to continuously rise to the upper end of the target range of 4%-4.25%. Banks are forced to frequently use the Fed’s emergency lending facility – a sign that liquidity is no longer abundant.

Lou Crandall, chief economist at Wrightson ICAP, said current market signals suggest the Fed is approaching a “dangerous” point, with all the warning systems in the cockpit flashing.

Since April, the Fed has slowed its runoff to about $20 billion per month, including a maximum of $35 billion in mortgage-backed securities and $5 billion in government bonds. Many experts believe that with such a slow pace, the Fed could completely stop immediately to avoid financial instability.

“They could have continued for a few more months, but I personally think they should have stopped six months ago,” said Blake Gwinn, head of US interest rate strategy at RBC Capital Markets. “The benefits are not as great, and the volatility is increased.”

Still, some officials want the Fed to shrink further. Vice Chair of Banking Supervision Michelle Bowman has said she wants to aim for a “leaner” balance sheet than the 2022 target to reduce the Fed’s impact on markets.

In contrast, Governor Christopher Waller, who opposed slowing the runoff in March, now says reserves are approaching the “competitive” level between banks.

Stopping the shrinkage doesn’t mean the balance sheet will stand still. If the Fed’s liabilities, such as bank reserves, currency in circulation, or Treasury accounts, increase, reserves will continue to erode unless the Fed starts buying assets.

So, after the runoff ends, the Fed will have to decide when to start expanding its balance sheet again, and what types of assets to buy. According to many officials, the long-term goal is to hold only government bonds, which means continuing to let MBS mature without reinvesting.

Chỉ cách đây 2 tuần, Fed vẫn duy trì lập trường rằng sẽ đợi đến cuối năm 2025 để quyết định dừng quá trình “runoff”, tức là để các khoản nắm giữ chứng khoán đáo hạn mà không tái đầu tư, qua đó giảm quy mô bảng cân đối. Trong một bài phát biểu ngày 14/10, Chủ tịch Fed Jerome Powell cho biết thời điểm kết thúc quá trình này “có thể sẽ đến trong vài tháng tới”.

Tuy nhiên, những biến động gần đây trên thị trường tiền tệ, đặc biệt là sự gia tăng bất ngờ của lãi suất qua đêm, đang khiến nhiều nhà phân tích và quan chức Fed cho rằng thời điểm “hạ màn” có thể cần đến sớm hơn.

Việc thu hẹp bảng cân đối không trực tiếp liên quan đến chính sách lãi suất, mà là một phần trong nỗ lực kiểm soát lãi suất ngắn hạn – yếu tố ảnh hưởng trực tiếp đến vay tiêu dùng, vay mua nhà và tín dụng doanh nghiệp. Trong giai đoạn khủng hoảng tài chính 2007-2009 và đại dịch, Fed đã mở rộng bảng cân đối bằng cách mua vào một lượng lớn trái phiếu chính phủ và chứng khoán được đảm bảo bằng thế chấp (MBS).

Kể từ năm 2022, khi bảng cân đối đạt đỉnh gần 9.000 tỷ USD, Fed đã bắt đầu để các tài sản đáo hạn tự động rút khỏi hệ thống mà không tái đầu tư, kéo theo sự sụt giảm dự trữ ngân hàng.

Song, quá trình này đầy rủi ro. Nếu Fed thu hẹp bảng cân đối quá sâu, hệ thống tài chính có thể thiếu thanh khoản, như từng xảy ra năm 2019 khi lãi suất qua đêm tăng vọt, buộc Fed phải bơm tiền trở lại một cách vội vã và gây hoang mang cho thị trường.

Trong 3 năm qua, phần lớn dòng tiền rút ra đến từ cơ chế tiền gửi của các quỹ thị trường tiền tệ tại Fed. Nhưng hiện nguồn này gần như đã cạn, từ mức đỉnh 2.200 tỷ USD vào năm 2023 nay chỉ còn rất ít. Bắt đầu từ tháng này, mỗi USD đáo hạn sẽ được rút trực tiếp từ dự trữ của các ngân hàng.

Việc chính phủ Mỹ phát hành thêm trái phiếu gần đây đã rút thêm tiền ra khỏi hệ thống, khiến lãi suất liên ngân hàng liên tục tăng lên cận trên của biên độ mục tiêu 4%-4,25%. Các ngân hàng buộc phải thường xuyên sử dụng cơ chế cho vay khẩn cấp của Fed – một dấu hiệu cho thấy thanh khoản đang không còn dồi dào.

Lou Crandall, chuyên gia kinh tế trưởng tại Wrightson ICAP, cho biết các tín hiệu thị trường hiện nay cho thấy Fed đang đến gần điểm “nguy hiểm”, tất cả các hệ thống cảnh báo trong buồng lái đã sáng đèn.

.

Từ tháng 4, Fed đã giảm tốc độ runoff xuống còn khoảng 20 tỷ USD mỗi tháng, bao gồm tối đa 35 tỷ USD chứng khoán thế chấp và 5 tỷ USD trái phiếu chính phủ. Nhiều chuyên gia cho rằng với tốc độ chậm như vậy, Fed hoàn toàn có thể dừng ngay lập tức để tránh bất ổn tài chính.

Blake Gwinn, trưởng bộ phận chiến lược lãi suất Mỹ tại RBC Capital Markets, nhận định: “Họ có thể tiếp tục thêm vài tháng nữa, nhưng cá nhân tôi nghĩ nên dừng lại từ 6 tháng trước. Lợi ích mang lại không nhiều, trong khi rủi ro biến động lại tăng lên.”

Dù vậy, vẫn có những quan chức muốn Fed thu hẹp thêm. Phó Chủ tịch phụ trách giám sát ngân hàng Michelle Bowman từng phát biểu rằng bà muốn hướng đến một bảng cân đối “gọn hơn” so với mục tiêu 2022 nhằm giảm tác động của Fed lên thị trường.

Ngược lại, Thống đốc Christopher Waller, người từng phản đối việc giảm tốc độ runoff hồi tháng 3, giờ đây cho rằng mức dự trữ đang tiến sát ngưỡng “cạnh tranh” giữa các ngân hàng.

Việc dừng thu hẹp không có nghĩa bảng cân đối sẽ đứng yên. Nếu các khoản nợ của Fed, như dự trữ ngân hàng, tiền mặt lưu hành hay tài khoản của Bộ Tài chính, tăng lên, thì dự trữ sẽ tiếp tục bị “bào mòn” trừ khi Fed bắt đầu mua lại tài sản.

Vì vậy, sau khi dừng runoff, Fed sẽ phải quyết định khi nào nên bắt đầu mở rộng trở lại bảng cân đối, và sẽ mua vào loại tài sản nào. Theo nhiều quan chức, mục tiêu lâu dài là chỉ giữ trái phiếu chính phủ, tức tiếp tục để MBS đáo hạn mà không tái đầu tư.

Leave a Reply